We have to change the negative things into positive. In today’s Japanese film industry, we always say we don’t have enough budget, that people don’t go to see the films. But we can think of it in a positive way, meaning that if audiences don’t go to the cinema we can make any movie we want. After all, no matter what kind of movie you make it’s never a hit, so we can make a really bold, daring movie. There are many talented actors and crew, but many Japanese movies aren’t interesting. Many films are made with the image of what a Japanese film should be like. Some films venture outside those expectations a little bit, but I feel we should break them.

The above quote is from Takashi Miike. I know it because writer Warren Ellis shared it a few years back. I love it. Ellis used it in reference to Jack Kirby’s comic adaptation of 2001: A Space Odyssey for Marvel Comics. It was an apt reference there and I think it works for plenty of other creators who have transcended their circumstances to create work above and beyond what’s expected of them, their place in the pop culture hierarchy or their genre.

In this specific case, Miike was describing his own path to becoming one of the most daring filmmakers in the world today. I think it’s also a pretty good way to look at what director Seijun Suzuki was up to during his cinematic mad dash through the mid- 1960s.

I love the idea. Truly. If you don’t know if anyone is going to show up anyway or if you’re there just to fill out a double feature – why play it safe? Why not leave it all out there?

It’s not a perfect analog, of course. Suzuki’s circumstances were certainly different. Where Miike was commenting about his work at the edge of a film industry in decline, Suzuki was a contract director working during the commercial height of Japanese cinema. Still, the gap from what both were supposed to be producing and what they ended up producing is huge and in both cases driven by real creativity and a desire to escape the trap of expectation.

Suzuki was under contract with Nikkatsu in the 1960s; there to crank out genre pictures at a good clip to help fill out the studio’s slate. The thing is, his vision was such that he was consistently delivering much more than the standard genre fare the studio expected. His output during this period, in films like Gates of Flesh and Youth of the Beast, is full of unexpected, surprising moments and is marked by constant experimentation with everything- sets, story, editing, color and staging.

While this work had some commercial and critical success, the studio was increasingly uncomfortable with Suzuki’s films. They were just too weird. To be fair, most of his films would be weird to modern eyes. They tried to rein him in. For his next picture, they wanted something a little less on the edge.

The film that came out of this situation was Tokyo Drifter and, thankfully for us, Suzuki couldn’t be constrained by the suits at the studio. At some basic level he complied by their wishes. The plot is simple and moves from A to B in a brisk hour and twenty minutes. A gangster, Tetsuya (played by pop star, Tetsuya Watari) tries to go straight alongside his boss and they’re undermined by a rival. He ends up on the run and then returns to revenge himself against those who have wronged him. There are gunfights galore. If you squint, it’s like he was toeing the line. This has the general shape of a gangster picture.

Looking at the picture as a whole, however, it’s clear that he just couldn’t help himself. No matter what his bosses said, he wasn’t going to turn in a standard yakuza-eiga. Suzuki embroiders the film with details and flourishes that constantly surprise and delight.

Tokyo Drifter is often described as a “jazzy” film. There’s definitely a jazz vibe to it that draws the comparison, but it’s also like jazz in that Suzuki takes a basic gangster picture framework and, in effect, improvises to round out the basic skeleton with something much more interesting. It ends up being a glorious 80 minutes.

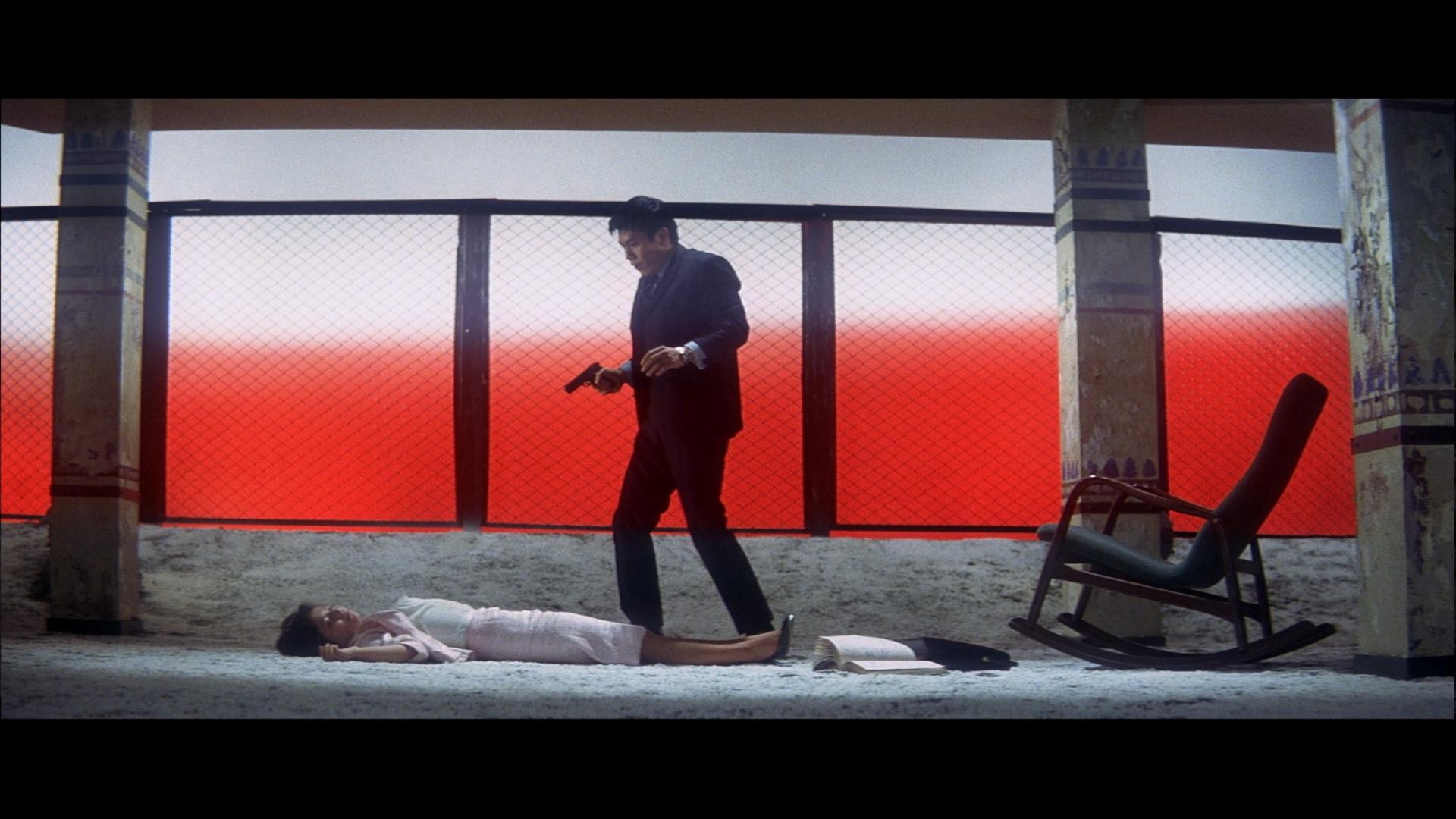

Take the use of color. At first blush, say, looking at stills or the trailer, you might think that this is like The Umbrellas of Cherbourg or something similar- an intentionally colorful film with that mid-1960s CinemaScope (here: Nikkatsuscope) feel. Except, it’s not just that. Colors in Tokyo Drifter are so present they’re like a separate character. From the start, when a seriously underexposed black and white opening gives way to spot color (red) there’s a constant play with color. For example, there are shots that are basically color fields. Yellow scenes appear throughout the film- almost wholly yellow scenes. Pink and purple scenes come along for the ride as well. The chapter titles on the Criterion DVD reference these color coded sequences.

There are also a number of shots that feature highly contrasting objects that bring a bright primary color accent to the frame. Elements like the villain’s red suit, a red telephone, the iconic blue suit of the hero and the red of a paper lantern contrasting against a field of snow add constant visual interest. Your eye is never let off the hook.

As was Suzuki’s way, Tokyo Drifter offers more than just the creative use of color to keep you off-balance. He was constantly experimenting. Structurally the film seems designed to keep the viewer off-balance. Time is incoherent and action is constantly balanced against music or uneasy humor. A tense scene early in the film is punctuated with a woman’s laughter as she reads a magazine. A fight scene later on in the film is matched with a melancholy scene of Tetsuya singing the title song on a soundstage. A foiled daytime kidnapping cuts, in the middle of the action, immediately to a mellow date scene at night in an arcade.

The art direction and framing are dazzling. Physical spaces are constantly manipulated within the frame. Characters are grouped or separated from one another by doorways, walls, fences and even a trap door. Soundstages and location work are also blended at will. Throughout the film the transition from realism to theatrical or even abstract staging is made from scene to scene or even shot to shot without warning. A gritty tour of Tokyo is matched immediately with a soundstage right out of an MGM musical.

To be sure, it’s not perfect cinema. The plot could be written on the back of a 3 by 5 card and the acting isn’t the greatest you’ll see from Japan in the 1960s (admittedly, that’s a pretty high standard.) But really, it doesn’t much matter. Within the system in which he was entrenched, Suzuki wasn’t going to make a perfect film. Tatsuya Nakadai wasn’t walking through the door and the schedule and budget weren’t going to get any bigger. But, that’s really the glory of the work Suzuki did in the 1960s. He took a system in which he wasn’t expected to do anything other than collect a paycheck and instead turned out unique, creative gems like Tokyo Drifter. His vision simply couldn’t be contained.

This article was originally published on the Brattle Film Blog in May 2016