Back in the day the Hong Kong film industry moved quickly. If a film broke new ground with a novel take on a genre or ushered in a whole new sub-genre; the rest of the industry would rush in to cash in on the trend. Every film industry does this, of course, but Hong Kong in the 1980s and 1990s was producing so many movies, with such a high concentration of talent, the effect was mesmerizing. People were one-upping each other at every turn.

The most familiar example is probably when John Woo’s hugely successful A BETTER TOMORROW (1986) ushered in an era of stylish and bloody triad films that dominated Hong Kong cinema for several years. Woo and others like Ringo Lam, Tsui Hark and even Wong Kar-Wai piled into the genre in a flurry of blood-soaked creativity. It was a glorious run.

The next most obvious example of this trend-hopping phenomenon crossed over with the first in time and talent and the two trends, taken together, were the driving force behind pushing Hong Kong cinematic style and talent to the forefront of the global movie scene.

In 1991, while all those bullets were flying around (the triad films peaked with Ringo Lam’s FULL CONTACT (1992)), Tsui Hark released ONCE UPON A TIME IN CHINA, a modern retelling of the story of Wong Fei Hung, starring the then relatively unknown Jet Li. The combination of Hark’s mature approach and Li’s stoic grace proved to be an unbeatable combination. The film was a huge hit and a new era of classy martial arts period cinema was born. In just a couple of years Hong Kong produced a series of excellent period martial arts movies that included all-time genre classics like Yuen Woo-Ping’s IRON MONKEY, ONCE UPON A TIME IN CHINA 2 (featuring both Jet Li and Donnie Yen), Corey Yuen-Kwai’s FONG SAI YUK and Wong Kar-Wai’s bewildering and beautiful ASHES OF TIME.

All that brings us to LEGEND OF THE DRUNKEN MASTER (originally released as DRUNKEN MASTER 2, a sequel to Yuen Woo-Ping’s glorious DRUNKEN MASTER (1978).) The trend for period martial arts pictures reached its zenith in 1994. Two films in particular put an exclamation point on the arc during that year- Gordon Chan’s FIST OF LEGEND, starring Jet Li and DRUNKEN MASTER 2.

FIST OF LEGEND, a retelling of the story of Chen Zhen (who many will know from Bruce Lee’s FIST OF FURY) is one of the best the genre has to offer and is one of the first I reach for when people ask for martial arts movie recommendations. It’s got everything- a great cast, a solid story, incredible martial arts sequences and an intense performance by one of the top stars the genre has ever produced.

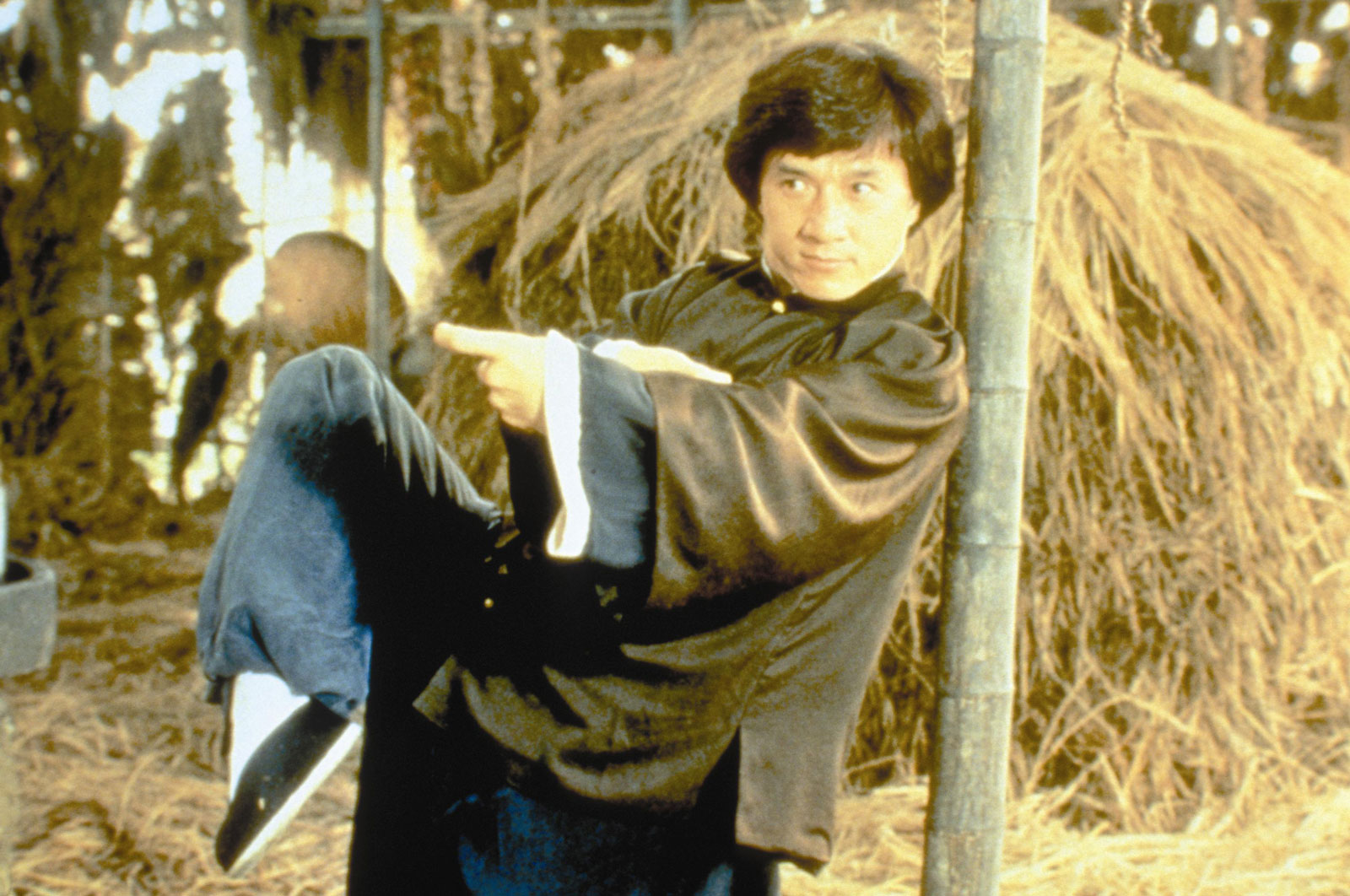

DRUNKEN MASTER 2? It too is one of the first I reach for when people as for recommendations although the reason in this case is much more straightforward. The reason? Simple. DRUNKEN MASTER 2 has the best overall fight scenes ever put on screen and he finale is probably the single best pure fight sequence ever filmed.

Before I wax poetic about the fights I have to mention one non-martial-arts related highlight of the film for me, the ultimate Hong Kong veteran actor Ti Lung as Wong Kei-Ying (Wong Fei Hung’s father) and Canto-pop sensation Anita Mui as his wife. It’s a bit of casting that’s fascinating on paper and ends up playing very well on screen.

Ti Lung’s career stretches from the late 1960s through to the present day. He got his start in RETURN OF THE ONE ARMED SWORDSMAN (1969,) part of an important series in the development of the genre, and went on from there to be a featured actor for the important Shaw Brothers Studio director Chang Cheh (FIVE VENOMS, FIVE ELEMENT NINJA) throughout the 1970s. In 1986 he was one of the stars of A BETTER TOMORROW alongside the “God of Actors” Chow Yun-Fat. His performance in DRUNKEN MASTER 2 transcends the expectations of the role. Wong Kei-Ying purpose in the film is to be a mature foil to the antics of Chan’s Fei-Hung. He needs to instill fear and be stern. That’s it. He could be forgiven for mailing in his performance. He doesn’t. He plays the role with surprising intensity and the few flashes of his martial arts prowess remind you of his unimpeachable pedigree.

Anita Mui, who sadly passed away in 2003, was one of the biggest stars in Asia for more than 20 years. Her musical career had her named the “Madonna of Asia” back when such comparisons meant something and her film career included many highlights from the golden era of Hong Kong cinema. Her performance here is as charming as it gets. Her stage persona was as sexy as it gets (hence the Madonna comparisons.) On-screen she could be sexy, for sure, but she could also be very funny. Here’s she’s given free rein to ham it up and the results are as close to scene-stealing as anyone ever gets in a Jackie Chan film.

Anita Mui, who sadly passed away in 2003, was one of the biggest stars in Asia for more than 20 years. Her musical career had her named the “Madonna of Asia” back when such comparisons meant something and her film career included many highlights from the golden era of Hong Kong cinema. Her performance here is as charming as it gets. Her stage persona was as sexy as it gets (hence the Madonna comparisons.) On-screen she could be sexy, for sure, but she could also be very funny. Here’s she’s given free rein to ham it up and the results are as close to scene-stealing as anyone ever gets in a Jackie Chan film.

Now, the fights.

A lot of words have been written about the finale of this film. That’s deserved. This centerpiece fight between Jackie and his real-life bodyguard Ken Lo is a brilliant, visceral classic. I’ve watched it five times this week and have seen it dozens of times over the past twenty years and I still notice little things about it that surprise me.

The finale is a pure distillation of everything Jackie had been doing since he’d started to take direct control of the action in his moves in the 1980s. While there’s not much in the way of props or acrobatics and the only stunt is Jackie jumping into a fire pit, the core elements of Jackie’s choreography are all present. It’s two physically gifted screen fighters going toe to toe for half a reel- a half a reel that took three months to shoot.

The finale is a pure distillation of everything Jackie had been doing since he’d started to take direct control of the action in his moves in the 1980s. While there’s not much in the way of props or acrobatics and the only stunt is Jackie jumping into a fire pit, the core elements of Jackie’s choreography are all present. It’s two physically gifted screen fighters going toe to toe for half a reel- a half a reel that took three months to shoot.

In their own way the other fights in the film are nearly as good. They’re different, and there’s a very good reason for that, but they’re also the culmination of a long history of martial arts film-making.

Why they’re different requires us to take a step back and talk about the titular director of this film, Lau Kar-Leung. Lau, director of two of the greatest martial arts movies of all time, LEGENDARY WEAPONS OF CHINA and 36th CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN, was, on-paper, a dream director for this film. A sequel to one of the highlight films of the 1970s directed by the greatest director of the legendary Shaw Brothers Studio? How great would that be? The answer is actually really great, although the process of getting there was contentious. How contentious? While it’s not credited that way, Drunken Master 2 really had two directors and two corresponding styles of fight choreography.

It’s true. The first 70 minutes are basically Lau’s and the fights are traditional 1970s choreography implemented with a huge budget, a ton of time and the best stuntmen and women in Hong Kong. The results are absolute genius. They’re not the same visceral thrill ride of the finale, but they are precise, rhythmic and beautiful. Chan’s athleticism and coordination are put through their paces in a smaller, but no less impressive way throughout the film.

From the initial fight with Lau himself sparring with Chan to a blistering drunken boxing segment with Chan facing off against multiple opponents halfway through the film, the Lau directed fights are the ultimate expression of the traditional “kung fu” style that the Shaw Brothers Studio made famous in the 1970s.

The thing is, that traditional style, as good as it was, didn’t sit well with Jackie. He pushed for more of his own modern style and Lau, being one of the greatest martial arts film directors of all time, wasn’t about to wave the white flag for anyone. These differences led to Chan taking over for the finale.

It’s rare that this kind of conflict turns out to have a positive effect on a film, but in this case it certainly did. We got two-thirds of Lau Kar-Leung at the height of his powers directing the best stunt-men in the world and then we got a finale where an insanely talented perfectionist was let loose for months to create a masterpiece.

That’s my kind of two-for-one deal.

This article was originally published on the Brattle Film Blog in 2016.